The Insurrection Act of 1807 and the Trump Coup d'Etat

Tomorrow (Easter Sunday) is the deadline for Hegseth's "report" after which Trump may declare martial law. That's martial law in the United States.

I. The Path to Power

When authoritarian individuals/movements set out to take over a country, they don’t always do so by means of an illegal, or a violent, campaign. More often they begin by pitching themselves as ordinary political parties, with a platform and policies which place them at odds with the (then) mainstream parties. They remain within the law, and usually use the power of the law—in what might be called a “ju-jitsu” fashion—against itself. Such tactics may, but don’t always, take them into or close to political power. Many examples could be cited of this tactic.

Authoritarian movements and individuals, however, differ from constitutional individuals and movements primarily in that it is never their intention to follow the democratic process. It is never their plan to submit themselves as officials—and their policies as a program of government—to the electoral process and, if the vote goes against them, to leave office. The single most significant defining characteristic of an authoritarian movement is that authoritarians consider that they, and they alone, have the right to govern, and that, having made that claim, whatever actions they might take to gain and hold power are wholly justified:

“He who saves his Country does not violate any Law.” – President Donald J. Trump, 15 February, 2025, on X.

No laws apply to them, they believe. Anyone who disagrees with them isn’t merely wrong, they are going against the natural order of being, whether that order is defined in religious terms, in economic terms, in political terms, or in terms of some other ideological category. Such dissidents, they believe, cannot be allowed to persist in society, so must be removed: forced out or exterminated.

When an authoritarian individual or movement achieves power, the law is replaced with the will of the leader in a dictatorship or the leadership in an oligarchy. It becomes whatever the ruler or leadership says it is at any given moment. Such rulers, whether they term themselves kings, emperors, first citizens, presidents, prime ministers, or any other titles that take their fancy, are sole and absolute despots.

II. The Consolidation of Power

Once an authoritarian has gained power, usually by some perversion of a previously established legal and peaceful process, power must be consolidated in such a way as to prevent anyone else from following the same route. The pattern is this: would-be dictators allow, if they don’t foment, disorder to grow—disorder they then use as an excuse to declare a state of emergency. They then use the measures, most notably martial law, that allow them to suppress all dissent by the use of legal, often lethal, force, shutting down the institutions of representative government and seizing total control.

Mussolini and the Fascists

Mussolini’s rise to power began after his return to civilian life in 1917, by which time he had abandoned socialism and begun to promote the ideology which he named fascism. At that time, he joined a group in Milan, one of many such fasci, which at the time meant union, band, or league. Fasci were found throughout Italy from the 1870s onward.1

In March of 1919, he re-formed this group as the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento or Italian Combat Squad.2 Popularly known as the Blackshirts from their uniforms, they engaged in street fighting with similar gangs of Communists.3 In 1920 and 1921 the Fascists grew rapidly in numbers and began to deploy systematic political violence; they also expanded from their small urban origins to a mass movement which also embraced the countryside.4

In May of 1921, Mussolini and 37 other Fascists were elected to the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the Italian parliament, thanks to the belief of elderly Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti that, by including them in his coalition, he could tame them.5 This did not work. Now Mussolini and the Fascists schemed against the other coalition parties, and from those within the Chamber of Deputies, with the same goal as before: to take full control of the government of Italy.

In February 1922, the majority of the Italian non-Catholic left-wing parties, the Socialists, the Italian Socialist trade union (the CGL), the remaining independent revolutionary syndicalists, anarchists, and republicans, formed an alliance, the Alleanza del Lavoro (Labor Alliance), to resist Fascism. But what they would not do was to hold discussions with the liberals. Instead, they attempted a protest, a defensive “legalitarian strike” that demanded a return to the “law and order” they had rejected two years earlier. The outcome of this strike was that just as the moderates had begun to take alarm at the spread of Fascism in the north of the country, their fear of the “Red menace” was re-awakened. The strike lasted from 1 August to 3 August and was followed by five days of Fascist reprisals.6

The government of Prime Minister Luigi Facta was split into three subgroups in relation to the Fascists: those who wanted to bring the Fascists into the government, those who were ready to resist such a move with force, and those who wanted to resist, but without the use of force. Mussolini, aware of this split within the government, and of the fear of a leftist coup d’etat (however unrealistic that fear may have been), realised that this was the moment to make the decisive move. With the rest of the Fascist leadership, he began planning a massive march on Rome.

While some party radicals urged an outright coup, moderate and conservative Fascists (now led by Grandi) opposed the new strategy to force the creation of a Mussolini-led coalition government, but they were overruled. Action began on October 27 with direct Fascist takeovers, most without violence, of many police headquarters, community centers, and even arsenals in north and north-central Italy. The plan was to concentrate about 25,000 squadristi in Rome as a display of force, without any intention of attempting a coup—even though twenty-five small Fascist arditi squads were being organized for minor terrorist acts should further pressure was needed.

There was not the slightest danger of a violent Fascist coup against the government itself. Not only had no plan for this been developed, but also the army and police forces outnumbered the fascists to be concentrated in Rome, and the district commander, General Pugliese, was prepared to execute any order given by the crown. Leaders of the Italian Nationalist Association also assured King Victor Emmanuel that their own Sempre Pronti militia was ready to fight the Blackshirts, if requested. As far as economic interests were concerned, leaders of the Confindustria (the industrialists’ association) would have preferred a strong government led by Giolitti, though they liked the current Fascist economic program and would accept a new coalition government with some Fascist participation.7

When King Victor Emmanuel II refused to grant a decree of martial law, the Facta government resigned. The king then sought to resolve the crisis by asking the conservative pro-Fascist liberal Antonio Salandra to form a coalition that would include Mussolini and a few other Fascist ministers. Mussolini, remaining in the north near Milan, was intransigent on the issue of becoming prime minister himself, however, and by the morning of the 29th Salandra gave up further efforts to organize a new government. The Fascist contingency plan was to form an alternative revolutionary government in the north if denied power in Rome, but on the night of October 29 Victor Emmanuel invited Mussolini to come to Rome to lead a new parliamentary coalition. The Fascist leader arrived in the capital the next morning. The Blackshirts waited outside the city for two more days, then entered Rome in a victory parade on the 31st. Thirteen people died in the violence that ensued.8

Thus, by creating a fake emergency—the March on Rome, intended not as a coup but as a political pressure tactic, and by making an outrageous demand to be made Prime Minister—Mussolini created a crisis of government. By promoting himself as the solution to that crisis, by becoming Prime Minister legally, through the ju-jitsu movement of using the legal system against itself, he brought an end to the rule of law in Italy.

Hitler and the Nazis

In spite of the fact that their interests initially clashed over Austria, it is clear that Hitler admired Mussolini and that he carefully studied Mussolini’s organizational methods and political tactics. This served Hitler well during his early years, and it is a matter of record that this man who betrayed so many remained loyal to Mussolini to the end.

Following the parliamentary elections of July and November 1932, the Nazi Party had the largest number of seats in the Reichstag, the German parliament of the Weimar Republic, but not enough to form a government on its own. The president of the republic, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, a member of the old aristocracy as well as one of the most highly decorated soldiers of Bismarckian Germany, did not hold Hitler in high esteem, to say the least, mainly due to class prejudice.

But like all the other conservatives of the day, he believed that the conservative politicians could restrain his worst impulses and so, reluctantly, Hindenburg appointed Hitler Chancellor on the understanding that he would form a coalition government with the German National People’s Party (DNVP), led by Alfred Hugenberg. This Hitler did, but he carefully placed his chief lieutenants, Wilhelm Frick as Minister of the Interior and Hermann Göring as Minister of the Interior of Prussia, to put Nazis in charge of the law enforcement agencies of, respectively, the country as a whole and the key province within the country.

From the Nazi standpoint, this was a tremendous step forward, but it still left them vulnerable to a political ouster by the conservative parties. It was essential, therefore, that they should oust the conservatives and consolidate all power in their own hands, and specifically in Hitler’s hands. The DNVP, however, continued to manoeuvre behind the scenes to form a coalition with one of the other parties to form a majority government and oust the Nazis. Clearly, the Nazis needed something special, an incident of some kind which would enable them to consolidate power in their own hands and eliminate any future challenges.

At this moment exactly, the incident they needed occurred: the Reichstag building caught fire and burnt to the ground. A young Communist from the Netherlands, Marinus van der Lubbe, was arrested and charged with arson, tried, and executed. Although most historians now believe that Van der Lubbe did set the fire, and that he acted alone, this has never been conclusively proved. Regardless of the truth of the matter, the Nazis drafted an Enabling Act, which became known as the Reichstag Fire Decree of 28 February 1933, which was signed by Hindenburg. This act suspended basic rights and allowed detention without trial. This was possible under Article 48 of the Weimar constitution, which gave the President the power to take emergency measures to protect public safety and order.9

But even this didn’t succeed in finally consolidating all power in the hands of the Nazis. A further parliamentary election on 6 March 1933 increased the Nazi share of seats to 43%, but this still necessitated a further coalition with the DNVP.

To achieve full political control despite not having an absolute majority in parliament, Hitler's government brought the Ermächtigungsgesetz (Enabling Act) to a vote in the newly elected Reichstag. The Act—officially titled the Gesetz zur Behebung der Not von Volk und Reich, the “Law to Remedy the Distress of People and Reich”—gave Hitler's cabinet the power to enact laws without the consent of the Reichstag for four years. These laws could (with certain exceptions) deviate from the constitution.10

Since it would affect the constitution, the Enabling Act required a two-thirds majority to pass. Leaving nothing to chance, the Nazis used the provisions of the Reichstag Fire Decree to arrest all 81 Communist deputies. In spite of their virulent campaign against the party, the Nazis had allowed the KPD to contest the election.11 The Nazis also prevented several Social Democrats from attending.12

On 23 March 1933, the Reichstag assembled at the Kroll Opera House under turbulent circumstances. Ranks of SA men, the Storm Troopers, served as guards inside the building, while large groups outside opposing the proposed legislation shouted slogans and threats towards the arriving members of parliament.13 After Hitler verbally promised Centre party leader Ludwig Kaas that Hindenburg would retain his power of veto, Kaas announced the Centre Party would support the Enabling Act. The Act passed by a vote of 444–94, with all parties except the Social Democrats voting in favour. The Enabling Act, along with the Reichstag Fire Decree, transformed Hitler's government into a de facto legal dictatorship.14

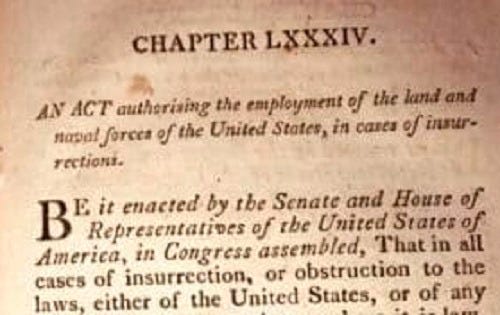

III. The Insurrection Act of 1807 and the Project 2025-Trump Coup

“But this momentous question, like a firebell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror.” —Thomas Jefferson

In the present case in the United States, reporting says15 that this tactic, in the form of the invocation of the Insurrection Act of 1807, is already being considered in relation to the immigration “emergency” along the Southern border. It is crucial to understand that once such a state of national emergency has been declared, and military measures have been legally authorized, such a “state of emergency” can then be extended to cover whatever is deemed necessary by the leader.

Watching the reports of demonstrations16 all across the continental US, including Alaska, against what Trump and his associates are doing to the United States, I am minded to suspect that the next thing he will do, in response to the demonstrations, will be to carry through on his threat to invoke the Insurrection Act, initially to “control the border” but then, more widely, “to restore order.”

IF he does this, it would be the crunch point. If the military accepted it as a legal order, and went along with it, then the coup d'etat would be complete.

IV. What Is To Be Done?

This is NOT an argument for doing nothing. There is nothing inevitable about this. It is possible that Trump and his associates might decide not to invoke the Insurrection Act. They might seek to use some other means to mobilize the military and law enforcement against the citizens, or they might turn out to be dedicated to the cause of democracy after all.

In this case there is nothing which would make me happier than to be proven by events to be wrong. But if this is what he does, then we must not accept it as the end. Nor must we “roll over and play dead,” waiting for the Trump administration to implode of its own accord.

On the contrary, public and peaceful demonstrations of dissent are essential. It must be made crystal clear that WE DO NOT CONSENT. We must speak out, stand out, march, demonstrate, and RESIST in whatever way we can. Only by causing as much “good trouble”—as the great John Lewis put it—as we can muster can we cause that implosion.

Rupert Chapman

26 March, 2025

Payne 1995:81.

Payne 1995:90.

Payne 1995:95-96.

Payne 1995:96-99.

Payne 1995:99.

Payne 1995:107.

Payne 1995:108.

Payne 1995:108-110.

“Adolf Hitler.” Wikipedia.com

Shirer 1960:198.

Evans 2003:335.

Shirer 1960:196.

Bullock 1999:269.

Shirer 1960:199. “Adolf Hitler,” Wikipedia.com.

Wagner 2025.

Verma, P. and Thadani, T. 2025. Bacon, J., Waddick, K., and Ortiz, J.L. 2025. Detzell, A. 2025.

Bibliography

Bacon, J., Waddick, K, Ortiz, J.L. 2025 “'People are feeling galvanized': Anti-Trump protesters rally in cities across US”, USA Today, 5 February (updated).

Bullock, A. 1999 [1952]. Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, New York, Konecky & Konecky.

Detzell, A. 2025 “Activists plan nationwide protests against Trump agenda for International Women’s Day : The mobilization effort encourages people to “create the networks we’ll need to resist fascism and the takeover of our freedoms.” MSNBC, 7 March.

Evans, R.J. 2003 The Coming of the Third Reich, New York, Penguin Books.

Payne, S. 1995 A History of Fascism 1914-1945, Madison, Wisconsin, University of Wisconsin Press.

Shirer, W.L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York, Simon and Schuster. 1960.

Verma, P, and Thadani, T. “Anger at Elon Musk turns violent with Molotov cocktails and gunfire at Tesla lots.” Washington Post, 8 March.

Wagner, Brett. 2025. “Is Trump preparing to invoke the Insurrection Act? Signs are pointing that way.” San Francisco Chronicle, 5 March 2025.