Still Waiting for Sherlock?

Further Adventures with Brilliant, Mentally Sketchy Guys

Sherlock Goes Missing

There he is, our favorite obsessive-compulsive, manic-depressive, high-functioning sociopath, the BBC’s version of Sherlock Holmes, acted by Benedict Cumberbatch. With a Calabash pipe, deerstalker hat, violin, 7% solution and trusty sidekick—Dr. John Watson, portrayed by Martin Freeman—he solves the most baffling of crimes. Our beloved net-tech comes with a splendid cadre of partners in crime. Co-starring are smarter older brother Mycroft (Mark Gatiss) and the deliciously evil villain James Moriarty (Andrew Scott). Supporting are delightful former-exotic-dancer-turned-granny-housekeeper Mrs. Hudson (the late Una Stubbs) and smitten forensic pathologist Dr. Molly Hooper (Louise Brealey).

Last seen on January 15, 2017, Sherlock has gone missing. He has done this before. Since the BBC’s Sherlock debuted in 2010, its writers, Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, have managed four seasons, with clusters of episodes appearing every 18 months or so, with painful droughts in between. However, the final episode of Season 4 played like a series end, and some surmised that Sherlock was off to beekeeping before his time.

Is there hope? Doubtful. News flashes claiming to have a release date for a mythical Season 5 are always fake news and the cruelest form of click-bait.

Among the better rumors is the one, several years ago, in which Andrew Scott (Moriarty) tossed us a proverbial crumb, leaving room for a new season but acknowledging that it would be at least “another couple of years away.[1] PANTS ON FIRE! Dangle that carrot, Andrew!

In 2022, Gatiss said he was “cautiously optimistic” that more Holmesian rascalry might come, but he had not a shred of evidence for it and could even guess when.[2]

But hope springs eternal. In January 2023, in an interview with BBC's Today, Sherlock co-writer Steven Moffat said he would “start writing tomorrow,” if Cumberbatch and Freeman agreed to come back. “They’re on to bigger and better things but, Martin and Benedict, ‘please come back?’”

So, we’re to wait for their schedules to clear—is that it? Oh, please!

And there’s something else hidden in Moffat’s words: he and Gatiss are not yet writing Season 5 because they have no commitment from their stars. Ergo, there’s no deal to report and no release date to presume.

To sum up, it’s now been six years—six bloody years!—and we have had nothing—bloody nothing!—from these people!

Therefore, as a humanitarian act for my fellow Sherlockians, I offer you three movies that will slake your thirst for bright, mentally sketchy guys, and I predict you will be pleased. All three of these films were made between 1957 and 1962, when films featuring unhinged male character archetypes were embraced by the industry. As we’ll see, one of these films has a spectacular remake coming four decades after the original.

But first, a word from our friends the Jungians.

The Mind Playing Out Upon a Screen

It’s been axiomatic for about 75 years now—since Carl Jung and his colleagues began to analyze film—that emanations of the collective unconscious (and perhaps the cultural unconscious, too) seep into consciousness through some of the movies we see. Jungian academic Glen Slater notes that we may be as likely to get stereotypes as archetypes in film.[3] But when we do get well-crafted figure-images from the deep layers of the mind, they are immensely powerful. They can cast light into the darkest corners of the psyche and engender profound wisdom about who we are – both the good and beautiful in us and the shadowy and truly evil in us.

On the downside, Birth of a Nation can teach a person a very great deal about true malevolence in fewer than two hours. Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda films were splendid works of film craft, but they were bent to the will of a failed painter who exterminated millions: Hitler.

There are finer uses of cinema, however. Appropriating the personal and civil rights of the great writer, director, actor, or actress, the Autonomous Creative Force (no kidding) “possesses” the genius mind and delivers a character, a story, or a spectacular artistic performance of such depth that it transforms us. Although the cinematic work of art is fiction, it is somehow more real than fact. It is archetypal—in and of and about all of us. Films of deep archetypal inflection move us: they teach us, warn us, and awaken us. Sometimes they even heal us.

This, then, leads to a kind of public psychiatry in which a film may allow us to examine—safely, as, thank god, that’s not me up there!—the bedrock neuroses we may encounter in the people we meet out there or (heaven forbid) within ourselves. We watch, in part, to explore the dark shadow elements—which eventually become light, if all goes well—that force themselves upward from the deep cauldron of trauma and destiny that is the unconscious mind. Flickering upon the screen are archetypal images of the good father (Zeus), the Aphrodite replicant (Marilyn Monroe), the Christ-figure of the self-archetype (Guillermo del Toro crafts many of these), or … the obsessive male.

This last one is a dangerous creature, most especially to himself. Our man is utterly the prey of his inability to relativize his cravings for the very things that will destroy him. He usually dies, but long before he winds up on a slab, he’ll be well and truly pestled to a paste.

Which is sad, of course. And, when it's fiction, it can also be fun. And that brings us back to ...

High-Functioning and Obsessive-Compulsive Sociopaths

Sherlock Holmes—of the Cumberbatch batch—is the contemporary poster child for the virgin high-functioning sociopath who doesn’t give a damn if he hurts you or not. His smarter older brother Mycroft, who secretly runs the British Empire, is the Western-civilization personification of OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder. Will they solve every crime? Of course! Am I certain? Well, no … but …

Balance of probability, my friends. Balance of probability.

So, whilst we are being denied our Sherlock, I summon from the ethers three obsessive males who are so entrancing that we marvel at the writers who crafted them, stand amazed at the actors who performed them, and bow before the directors who brought them to life. I offer you:

Sir Alec Guinness as Lt. Colonel Nicholson

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

Columbia Pictures. Directed by David Lean. Oscars (7): Best Picture, Director (Lean), Actor (Guinness), Screenplay, Cinematography, Music, Editing. With brilliant performances by Sessue Hayakawa and William Holden. Rotten Tomatoes: 94%. AFI 100 #13.

Lt. Colonel Nicholson is the epitome of the stiff-upper-lipped British officer. He finds himself responsible for maintaining the morale and discipline of a group of British soldiers in a hell-on-earth World War II Japanese prison camp along the River Kwai in Burma. The one remaining gap in a Japanese military supply route, the Kwai must be bridged, and the Japanese keep failing at it.

To shore up his men’s spirits, Nicholson takes over construction, and he and the inmates— who are now running the asylum—design and build a stunning span. Obsessed with perfection and taking a fatally misguided pride in the project, Nicholson entirely loses sight of his principal duty.

While the light colonel builds a bridge, an Allied team moves overland through heavy jungle to destroy it. As the team lays explosive charges, they find Nicholson defending a bridge he’s built for the enemy, rather than fighting for the future of Western civilization. Only in the moment before he dies does Nicholson awaken from his obsessional coma and attempt to help.

Gorgeous cinematography, a poignant performance by Sessue Hayakawa, and an unforgettably brilliant, brave, blind, and quintessentially self-deluded military character—make this film an incredible journey of insight.

Peter O’Toole as T. E. Lawrence

Lawrence of Arabia (1957)

Columbia Pictures (Horizon II). Directed by David Lean. Oscars (7): Best Picture, Director (Lean, again), Cinematography, Set Decoration, Sound, Editing, Music. Also starring the Rub-al-Khali, the world’s most treacherous desert. Rotten Tomatoes: 97%. AFI 100 #5.

Despite the fact that Peter O’Toole didn’t win a Best Actor Oscar for his performance in this role—the statuette went to Gregory Peck for his Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird—Premiere Magazine calls Peter O’Toole’s performance as T. E. Lawrence the best achievement by an actor or actress in film history.

T. E. Lawrence wasn’t universally loved. His critics called him the “Wild Ass of the Desert,” and that he certainly was. A polymathic genius without a day’s combat training, Lawrence wrested Arabia from the internecine squabbles of tribal warlords and won World War I in the Middle East, driving north as far as Damascus. In the process, he shaped the future of Arabia and the contemporary Near East.

He also went mad. Captured, beaten to a bloody pulp, and sexually assaulted by the Ottomans, Lawrence, whose masochism showed early in life after beatings by his mother, became both obsessively masochistic and sadistically vengeful during his sojourn in the desert. He suffered psychological disfigurement for the rest of his life. The scene in which Lawrence professes pleasure at the deaths of others is one of the most emotionally wrenching ever filmed.

When Lawrence died in a motorcycle accident at 46, Sir Winston Churchill grieved that the British Empire was “impoverished” by his passing. Robert Bolt’s extraordinary screenplay and deeply insightful characterization of this mad genius made him immortal.

James Mason as Humbert Humbert

Lolita (1962)

MGM. Directed by Stanley Kubrick. Oscars: Zip. Rotten Tomatoes: 95%.

The brilliant Vladimir Nabokov wrote both the book and the screenplay. What makes the film unforgettable is the performance of James Mason as a stolid academic consumed, body and soul, by a 12-year-old nymphet named Lolita (Sue Lyon). Suzy Izzard once called James Mason’s pipes the Voice of God,[4] and his famously silvery intonation makes his expression of a man shredded by the most heartless of muses all the more memorable. Lolita is carnal knowledge dragged to its most debased depths. This man sells his soul to the Devil for this girl.

This, the original version of Lolita, shocked film audiences in the early 1960s, on the eve of the Sexual Revolution and the Women’s Liberation Movement, for in those days a Valium-laced, kaffeeklatch mentality still held sway. The impact of the literal and cultural censorship of the day straight jacketed Stanley Kubrick, severely limiting what he could show. Had he known how bad the censors would get, the director said, he’d never have tried to make the film.

Mason’s performance is a classic. Peter Sellers does some remarkable shapeshifting. And Sue Lyon (Lolita), who celebrated her fifteenth birthday during principal photography, holds her own with Mason, Sellers, and Shelley Winters—no small feat.

Nabokov’s screenplay, however, suffers from several grave mistakes. The brilliant but distracting scenes that showcase the chameleonic genius of Peter Sellers, as Lolita’s true crush Clare Quilty, derail its primary plot. Worse, the writer excised both the incidence of unbearable loss in Humbert’s adolescence that branded the scholar’s psyche with hebephilia for life—and the death of Lolita in childbirth at the age of 17—the two elements that gave the book such tremendous dimension. These crucial scenes provided both the context of Humbert’s possession and the final, fatal loss that ultimately kills him. Nabokov’s script robs Humbert of his desperation, ecstasy, and fear—and it also steals away the character’s poetic voice. These are errors that Stephen Schiff, the writer/director of the 1997 remake, will not duplicate.

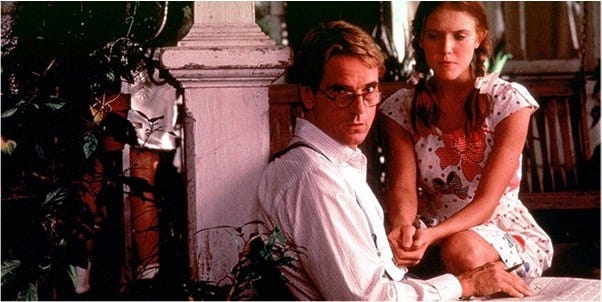

Jeremy Irons as Humbert Humbert

Lolita (1997)

Samuel Goldwyn Company. Screenplay by StephenSchiff from the novel byVladimir Nabokov. Directed by Adrian Lyne. With performances by Jeremy Irons, Dominique Swain, Melanie Griffith, and Frank Langella.

Offering the opinion that this is a better film than the original is blasphemous. People you don’t even know scurry about collecting the raw materials of your imminent demise: desiccated twigs and tree limbs, tins of Kingsford, and boxes of safety matches.

But it is a better film: The performance by Jeremy Irons is haunting and gorgeously modulated. Dominique Swain is half a dozen characters simultaneously—a beautiful, taunting, seductive, manipulative, and damaged sexually precocious child-woman. Her desperation shows in the cache of money she hoards for an escape and in an incidence of uncontrollable sobbing she endures after making love (if you can call it that) to Humbert.

Whereas the original film’s shooting script robs Humbert of his poetic voice, Schiff graces his damned scholar with the some of the most beautiful language from Nabokov's extraordinary book. In doing so, he provides Humbert with a character arc of traumatic imbalance leading to obsessional behavior leading to profound regret—and a strange, short-lived healing.

Schiff is almost perfectly true to Nabokov’s written words in Humbert’s last encounter with the teenager whose life he broke:

I looked and looked at her, and I knew, as clearly as I know that I will die, that I loved her more than anything I had seen or imagined on earth. She was only the dead-leaf echo of the nymphet from long ago—but I loved her, this Lolita, pale and polluted and big with another man’s child. She could fade and wither—I didn’t care. I would still go mad with tenderness at the mere sight of her face.”

And as Humbert waits upon a hill to be arrested for his brutal murder of Clare Quilty, he muses at the sounds coming from the mining town below him.

What I heard then was the melody of children at play, nothing but that. And I knew that the hopelessly poignant thing was not Lolita’s absence from my side, but the absence of her voice from that chorus.

This is a quintessential cinematic demonstration of Jung’s point that an archetype—and every truly archetypal character—is always, but always, both positive and negative simultaneously: Humbert was once a decent human being. Though tormented by the most agonizing of internal pressures, he remained a good man for a very long time. In Lolita’s presence, his will failed, and his psyche descended into its darker nature. He ends a manipulator, statutory rapist, liar, and killer. Still, he has the goodness to feel regret, to experience the impact he has had on her life. For her part, she has destroyed him in equal measure.

In the end, Humbert believes that the story he writes in prison will be the only immortality he and Lolita will ever know. And he is right. The rest, as Nabokov would say, is “rust and stardust.”[5]

Perhaps the strangest honor for a book or a film is to be banned. Esther Lombari of ThoughtCo assembled a list of the ten most-often-banned classic novels. It includes Ulysses by James Joyce, The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger, The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, The Color Purple by Alice Walker, Beloved by Toni Morrison, The Lord of the Flies by William Golding, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, and 1984 by George Orwell. And the last? Lolita.

Read the book. Then see both films. Then wonder, for a very long time, how Nabokov ever came by the insight to write such characters as these.

So, while those of us who are addicted to the public psychiatry of the obsessive male await our next opportunity to be “Sherlocked,” there is entertainment to be had in this flickering of films from the late 1950s and early 1960s, the same era that gave us the fabulous Don Draper and his menagerie of corporate beasties.

Am I certain that you’ll be amused? Pretty sure, actually.

“Why?” you ask.

Balance of probability, dear friends. … Balance of probability. …

[1] https://www.digitalspy.com/tv/cult/a830157/new-sherlock-couple-of-years-away-says-andrew-scott/

[2] https://www.looper.com/813118/mark-gatiss-reveals-the-truth-about-another-season-of-sherlock-exclusive/

[3] Slater, Glen. “Archetypal Perspective and American Film.” Spring: A Journal of Archetype and Culture, vol. 73, 2005: p. 11.

[4] Izzard, Suzy (as Eddie Izzard). Dress To Kill. Epitaph. Produced by Charlie Swanson, Eddie Izzard, Lawrence Jordan. 1999.

[5] Nabokov, Vladimir. The Annotated Lolita: Revised and Updated. With an introduction, preface, and notes by Alfred Appel, Jr. 1999: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. Location 5419.