Nuremberg Prosecutor Ben Ferencz Dies at 103

Ferencz, the Lead Prosecutor at the Nuremberg Einsatzgruppen Trial, Became a Tireless Champion for the International Rule of Law

He had wanted to be a World War II fighter pilot, but at 5’ 2” tall, Ben Ferencz—the infant immigrant who arrived in the United States at 10 months old from Transylvania, Romania—was so short his feet wouldn’t reach the pedals. He’d wind up doing something else. In 1943, the 23-year-old Harvard Law School graduate enlisted in the U.S. Army. His first job was as a typist at Camp Davis, but he couldn’t use a typewriter and wound up cleaning toilets, pots, and floors. By 1944, however, he had been assigned to 115th AAA Gun Battalion, an anti-aircraft artillery unit. He participated in the invasion at Normandy and in the Battle of the Bulge.

In 1945, he was transferred to the headquarters of General George S. Patton, where he was assigned to a team that collected evidence of war crimes. In that role, he was sent to the concentration camps that had been liberated by the U.S. Army. He was discharged from the Army on Christmas Day in 1945, but within weeks he was asked to return. He re-enlisted with the rank of colonel and was assigned to the Nuremberg Trials in Germany. He took with him his bride, Gertrude Fried Ferencz—his high school sweetheart and the love of his life—whom he married on March 31st, 1946.

Following the first Nuremberg trial of the twenty-one major war criminals in 1945-1946, twelve more trials were organized by the American authorities administering Germany.

These trials, known as the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials, took place between 1946 and 1949. The accused were also major war criminals, but they were of lower rank than the top-tier Nazi defendants tried first.

Each of the twelve Subsequent Trials involved defendants from individual “strands” of the Nazi state—industrialists, jurists, doctors, civil servants. One strand was the Einsatzgruppen—the mobile Nazi killing units that had operated in Eastern Europe. Ferencz had investigated and exposed them himself.

The scale of mass murder by the Einsatzgruppen was staggering. The killings began during the Nazi operations in Poland. The Einsatzgruppen machine-gunned tens of thousands of Jews. However, the Holocaust Encyclopedia writes that with the start of Hitler’s “war of annihilation” against the Soviet Union in 1941

the scale of Einsatzgruppen mass murder operations vastly increased. The main targets were Communist Party and Soviet state officials, Roma, and above all Jews of any age or gender. Under the cover of war and using the pretext of military necessity, the Einsatzgruppen organized and helped to carry out the shooting of more than half a million people, the vast majority of them Jews, in the first nine months of the war. [Emphasis added.]

It wouldn’t end there. The Einsatzgruppen followed Nazi storm troopers into every new Soviet territory they invaded, killing Jews in massive numbers in gassing vans or shooting them in large groups in graves they had made the Jews dig for themselves.

Ben Ferencz personally tallied their deaths using sequestered German documents. When he was certain of what he was seeing, he brought the case to Telford Taylor, the Chief Counsel of the Nuremberg Trials, arguing for prosecution. He encountered a court that was not only exhausted but also being pressured to end the trials to smooth the way for a post-war alliance between the United States and West Germany.

“I start screaming,” Ferencz told “60 Minutes” in 2017, recalling his conversation with Taylor. “I said, Look, I’ve got here mass murder, mass murder on an unparalleled scale. And he said, can you do this in addition to your other work? And I said, sure. He said, okay. So you do it.”

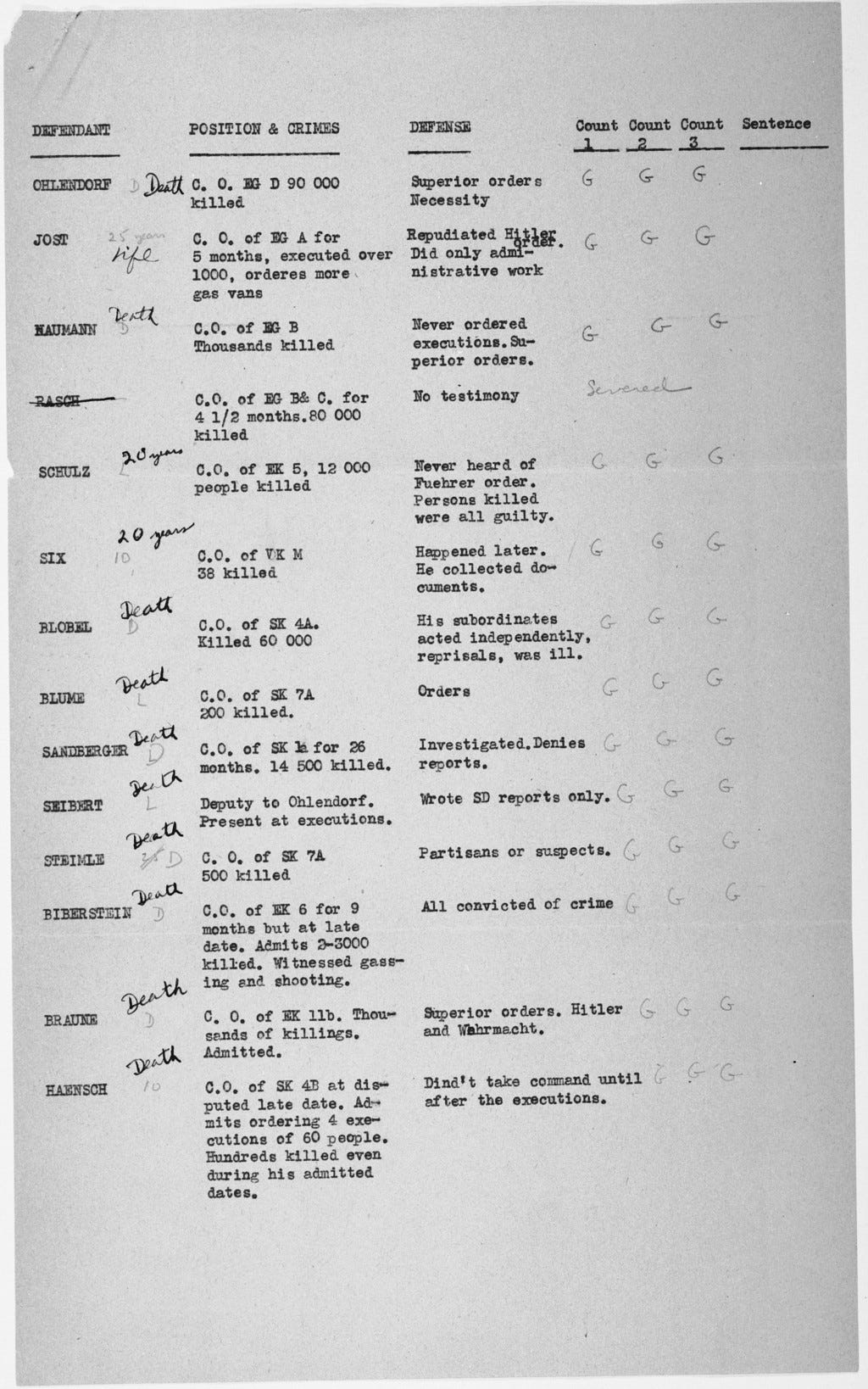

Ben Ferencz had just become the lead prosecutor of the largest murder trial in history. He tried 22 Einsatzgruppen commanders—though he said he could have indicted thousands. The initial tally at trial time indicated that the Einsatzgruppen had murdered a million Jews. Subsequent tallies raised that number to as many as two million Jews dead at the hands of the most vicious extermination brigade of the SS.

All of the defendants were convicted; four were executed. It was Ben Ferencz’s first courtroom trial.

As noted on BenFerencz.org, when the trials were over, Ferencz went to work for a group of Jewish charities attempting to help Holocaust survivors “regain properties, homes, businesses, art works, Torah scrolls, and other Jewish religious items that had been confiscated from them by the Nazis.” It was work that took years.

By the time he and Gertrude returned to the United States in 1956, they had four children—three girls and a boy. Ben went to work for the law firm of Brigadier General Telford Taylor, the former leader of the U.S. Enigma code-breaking team at Bletchley Park and his boss at the Nuremberg Trials. While Ben was still in Germany working on the return of stolen Jewish possessions and trying to ensure that reparations were paid, Telford Taylor was standing down McCarthyism at home. Both would question both the legality and the conduct of the Vietnam War—with Taylor going so far as to write Nuremberg and Vietnam: An American Tragedy, in which he argued that by the standards employed at the Nuremberg Trials, US conduct in Vietnam and Cambodia was as criminal as that of the Nazis during World War II.

By now, the Nuremberg Trials—and other tribunals for “seeking redress—not for revenge”—over the atrocities of the Axis Powers in World War II had closed down. Their disappearance left a gaping void in international law and justice. Ben Ferencz would spend the next 40 years advocating for international cooperation on war crimes, human rights, and crimes against humanity and an international court to administer justice.

In 2002, Ben Ferencz got his dream with the establishment of the International Criminal Court, seated at The Hague, though it came with no little disappointment. Several countries refused to become members. And although the Bill Clinton signed the so-called Rome Statute on behalf of the United States in his last hours in office, he attached so many detracting caveats that it was clear it would not be ratified.

Where Clinton merely damned with faint praise, George W. Bush went to war. Human Rights Watch counts the ways:

Bush unsigned the Rome Statute—by informing UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan that Bill Clinton’s signature was no longer valid.

Bush entered into Bilateral Immunity Agreements (BIAs) to “shield U.S. citizens from ICC prosecution in the event that these citizens are implicated in serious crimes on the territory of states that are subject to ICC jurisdiction.” Bush entered into more than 100 BIAs in just four years.

Bush instituted The American Servicemembers' Protection Act of 2002 (ASPA). If a country didn’t play ball with a bilateral immunity agreement, the US withheld military assistance, even in the case of “emerging democracies such as Benin, Croatia, and Mali, along with states across Latin America, including Bolivia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.”

The Bush Administration also inserted The Nethercutt Amendment into the Foreign Appropriations Bill, threatening over 50 governments with cuts in aid, including major allies such as Poland, which was in the "coalition of the willing," and Jordan, which was involved in training Iraqi police, should they not sign a BIA.

The Bush Administration pressed for and secured, in Security Council Resolutions 1422 (2002) and 1487 (2003), immunity before the ICC for personnel from non-ICC states involved in U.N. operations.

Perhaps Bush’s furor was related to Ferencz’s suggestion that not only should Saddam Hussein be tried for human rights abuses and war crimes, George W. Bush should, too. The Iraq War had been initiated by the US without permission by the UN Security Council. Further, Ferencz stated that Bush himself should be tried in the International Criminal Court for “269 war crime charges related to the Iraq War.” Clearly, the United States wanted immunity from this court for the Iraq War, as it would for the War in Afghanistan.

The Obama Administration warmed to the court, but the Rome Statute wasn’t ratified.

Trump went to war. Faced with investigations into possible rape and torture by U.S. troops in Afghanistan, the Trump Administration instituted a visa ban on ICC staff. In addition to travel bans, National Security Advisor John Bolton threatened prosecutions and financial sanctions against ICC staff, as well as against countries and companies assisting in ICC investigations of U.S. nationals.

Through it all, Ferencz’s position never wavered: law—national law, international law, all law—“must apply equally to everyone.” He believed that the “use of armed force to obtain a political goal should be condemned as an international and a national crime.”

Commenting on the 2013 U.S. assassination of Osama bin Laden, Ferencz wrote in the New York Times that the “illegal and unwarranted execution—even of suspected mass murderers—undermines democracy.” He made the same point about the 2020 assassination of Qasem Soleimani, writing that it was an “immoral action [and] a clear violation of national and international law.” Vladimir Putin, he said, should be “behind bars” for his crimes against the people of Ukraine.

All of his adult and professional life, Ferencz held that “war-making itself is the supreme international crime against humanity and that it should be deterred by punishment universally, wherever and whenever offenders are apprehended.”

His message, deceptively simple, was: “Law. Not war.”

Ben Ferencz was the recipient, Jim Slotek wrote, of a “mile-long list of awards”—among them the Erasmus Award, the Martin Luther King Peace Prize, the American Bar Association’s International Human Rights Award, the Florida Governor’s Gold Medal, and the U.S. Congressional Gold Medal.

Benjamin Berrell (nee Bela) Ferencz was born in Csolt, Transylvania, Hungary (now Romania) on March 11, 1920. He was married for 73 years—”without a quarrel”—to his high school sweetheart, Gertrude Fried Ferencz, who died in 2019. Ben and Gertrude had three daughters—Keri, Robin and Nina—and one son, Donald. Ben Ferencz died in Boynton Beach, Florida, on April 7, 2023. He was 103 years old and the last surviving prosecutor of the Nuremberg Trials.

Peace be the journey, Global Treasure.

What the history and brave men have done to teach us good or evil.

Thank you for sharing this , so we may honor what we can do to change anything.

We all have so much to learn from one another!

Thank you for this. How fortunate we were to have Ben Ferencz in our lives, always shining the Light, to which he has now returned.