In the Beginning: Christianity, Deism, and the Founding Fathers

The enlightenment revisited. A thorough primer on the creation of the United States as a SECULAR state.

No man shall be compelled to frequent or support religious worship or ministry or shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief, but all men shall be free to profess and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion.

-Thomas Jefferson. Excerpted from A Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom, drafted in 1777.

From the spectacular advance of freedoms of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s—even severely stressed, as they were, by the assassinations of JFK, RFK, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—a wellspring of profound hope rose that America would become the country we believed was envisioned by signers of the Declaration of Independence and the framers of the Constitution. Given that there is a mighty and dangerous culture war going on in America over the separation of church and state, with the Supreme Court coming down solidly on the side of religious control, a look back at what our Founders’ religious beliefs really were may be illuminating—and clarifying.

There were many who “founded” this country. There were 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence, and 39 signed the Constitution. There were two women—Abigail Adams (wife of John), acknowledged as one of the finest minds of her time, and Mercy Otis Warren, a prolific political playwright and pamphleteer who was one of the earliest advocates of a Bill of Rights—who were excluded from participating by their gender. And, of course, Lafayette arrived from France to fight with the Continental army at the tender age of nineteen.

But there are seven men who are largely credited with achieving the creation of the architecture of governance that would become the United States. They are George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison.

Currently, Christian religious conservatives in the United States are fond of saying that the United States was founded by Christians as a Christian nation. People like Josh Hawley—who has an Ivy League education and knows better—are outright lying about it for political purposes. The country was definitely not founded as a Christian nation. There were those who wanted it to be, but they lost.

But these days, both sides are engaged in what I call The Quote Wars. One side quotes one of the Founders, and the other side comes up with another quote by the same statesman that says, or appears to say, the opposite.

We’ll start here:

Religious Breakdown of the Founders

By far, the greatest number of the Founders were raised in one of the three most populous Christian traditions in the Colonies:

Anglicanism: George Washington, John Jay, and Edward Rutledge

Presbyterianism: Richard Stockton, Rev. John Witherspoon

Congregationism: Samuel Adams and John Adams (who eventually became a Unitarian)

Among the religions with fewer among their numbers:

Catholicism: Charles Carroll, Daniel Carroll, and Thomas Fitzsimmons

Quakers, Dutch Reformed, and Lutherans. Several of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and Constitution were from these denominations.

At first blush, it would seem that they were all raised Christian. That’s true; they were. But they didn’t all stay Christian, at least not all Christian and not even mostly Christian. Why? Because this was the Age of Enlightenment, and now they had a new religion.

Deism and the Founding Fathers

The Age of Enlightenment, which spanned the years 1685-1815 (the end of the Napoleonic Wars), was a period of profound scientific, political, and philosophical exploration, and one of its most extraordinary fruits was the religious school of thought called Deism.

Deism was based on the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Isaac Newton (who was originally an alchemist), John Locke and others. As Britannica notes:

Deists argued that human experience and rationality—rather than religious dogma and mystery—determine the validity of human beliefs. In his widely read The Age of Reason, Thomas Paine, the principal American exponent of Deism, called Christianity “a fable.” Paine, the protégé of Benjamin Franklin, denied “that the Almighty ever did communicate anything to man, by…speech,…language, or…vision.” Postulating a distant deity whom he called “Nature’s God”, Paine declared in a “profession of faith”:

I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life. I believe in the equality of man; and I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and in endeavoring to make our fellow-creatures happy.

Deism was widespread in the Colonies during the part of the 18th century when the Founders were essentially inventing a country. The Founders as a group were immensely well-educated, and Deism was profoundly popular in colleges during the period. But its influence did not stop there: Deism suffused virtually all of Revolutionary America. Outwardly, many deists maintained ties to the religions traditionally followed by their families, but their functional belief systems might be extremely unorthodox. This is partly the cause of the Radical Right’s claim that the Founders were Christian. On paper, that’s what they look like. That doesn’t mean they were.

Non-Christian Deism—Christian Deism—and Orthodox Christianity.

College of William and Mary endowed professor David L. Holmes writes that deism “inevitably subverted orthodox Christianity”—but how much?

In trying to determine how much Deism—or Christianity—affected the crafting of the United States, the trick is going to be understanding the degree to which a Founder’s religious beliefs were influenced by Deism. Dr. Holmes suggests a continuum comprising three categories: Non-Christian Deism, Christian Deism, and Orthodox Christianity (no Deism)—and suggests applying four criteria to determine into which of the three categories a Founder falls.

Church Attendance—but it’s dicey. Holmes points out that “colonial church served not only religious but also social and political functions, church attendance or service in a governing body (such as an Anglican vestry, which was a state office in colonies such as Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina) fails to guarantee a Founder’s orthodoxy.” Nevertheless, orthodox Christians would have attended church far more regularly than those heavily influenced by Deism.

Participation in Christian sacraments. Holmes points out that most would have been baptized as children, as participation in this sacrament was their parents’ decision, not theirs. However, adults influenced by Deism “had little reason to read the Bible, to pray, to attend church, or to participate in such rites as baptism, Holy Communion, and the laying on of hands (confirmation) by bishops.” Famously, George Washington refused to take communion as an adult.

Language used to refer to the divine. Here the three categories become more specific:

Non-Christian Deist: “Providence,” “the Creator,” “the Ruler of Great Events,” and “Nature’s God.” Note that the term Nature’s God appears in the Declaration of Independence. Examples: Ethan Allen, James Monroe, and Thomas Paine. Some, but not all, of the biographers of James Madison, who wrote the Constitution, put him in this category. Thomas Jefferson, who wrote the Declaration of Independence, falls somewhere between this category and the next. Largely during his lifetime, Alexander Hamilton belonged in this group, but later in life (and definitely on his deathbed) belonged in the category below. Benjamin Franklin described himself as a “thorough deist.”

Christian Deist: “Merciful Providence” or “Divine Goodness.” These are terms used by orthodox Christians, but Christian Deists don’t opt for the ones below. Examples: George Washington and John Adams.

Orthodox Christians: “Savior,” “Redeemer,” and “Resurrected Christ.” Examples: Patrick Henry, Elias Boudinot, Samuel Adams, and John Jay.

What do the Founders’ contemporary friends, family and especially clerics say about the Founder’s religious orientation and inclusion or rejection of Deism? Going back to the contemporary sources in the Founder’s life avoids the rank revisionism that seeks to strip the Deism out of the Founder’s life and re-vision it into a solely Christian context.

Dr. Holmes concludes that although orthodox Christians participated in every element of nation-building, a majority of the creators of the United States of America were Deists outright or had a Christian worldview heavily influenced by Deism.

In the end, the position of the United States on religion wound up in the First Amendment. Writes the Library of Congress:

Many Americans were disappointed that the Constitution did not contain a bill of rights that would explicitly enumerate the rights of American citizens and enable courts and public opinion to protect these rights from an oppressive government. Supporters of a bill of rights permitted the Constitution to be adopted with the understanding that the first Congress under the new government would attempt to add a bill of rights.

James Madison took the lead in steering such a bill through the First Federal Congress, which convened in the spring of 1789. The Virginia Ratifying Convention and Madison's constituents, among whom were large numbers of Baptists who wanted freedom of religion secured, expected him to push for a bill of rights. On September 28, 1789, both houses of Congress voted to send twelve amendments to the states. In December 1791, those ratified by the requisite three fourths of the states became the first ten amendments to the Constitution. Religion was addressed in the First Amendment in the following familiar words: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof."

In notes for his June 8, 1789, speech introducing the Bill of Rights, Madison indicated his opposition to a "national" religion.

Most Americans agreed that the federal government must not pick out one religion and give it exclusive financial and legal support.

This is not what Mike Johnson has in mind. More in this to come, but when Johnson says the Bible is his guide book and that his presence as Speaker of the House is ordained by God, he stands in direct opposition to—and sedition against—the Constitution of the United States.

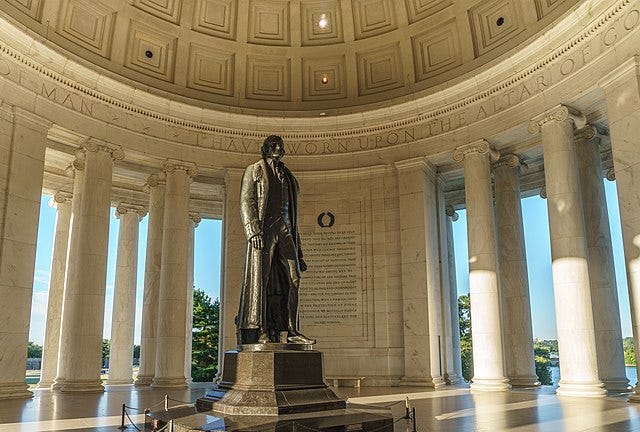

Or, back to Jefferson. This inscription, chiseled around the inner rim of the dome of the rotunda of the Jefferson Memorial, says it all.

"I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man."

—Thomas Jefferson, excerpted from a letter to Dr. Benjamin Rush, September 23, 1800.

That includes the tyranny of a singular, established national religion. Jefferson believed that freedom was a gift from God that could not be rightfully taken by any person or force from another—and that includes the denial of freedom by religion itself. Jefferson, and other Deists and Christian Deists, stood against the establishment of religion. There I stand also.

My curiosity is aroused by the absence of certain denominations, knowing of course that there is no numerical limit fixed by the words “Founding Fathers”. But we know the colonists included others. My own family tree includes one of the earliest Baptist ministers in Newport, Rhode Island, and I’ve long been amused that in part he was in Rhode Island because another branch of my family tree refused to allow Baptists into Massachusetts! Yet, no Baptists are represented in your lists. Perhaps there were theological/ideological conflicts with independence or the practice of law OR were they unable to take advantage of the advanced education opportunities at the centers for higher learning then existing?