Great Movies to Stream: Lolita--Both of Them!

The original was great. The remake is better by far.

James Mason as Humbert Humbert

Lolita (1962)

MGM. Directed by Stanley Kubrick. Oscars: Zip. Rotten Tomatoes: 95%.

The brilliant Vladimir Nabokov wrote both the book and the screenplay. What makes the film unforgettable is the performance of James Mason as a stolid academic consumed, body and soul, by a 12-year-old nymphet named Lolita (Sue Lyon). Suzy Izzard once called James Mason’s pipes the Voice of God, and his famously silvery intonation makes his expression of a man shredded by the most heartless of muses all the more memorable. Lolita is carnal knowledge dragged to its most debased depths. This man sells his soul to the Devil for this girl.

This, the original version of Lolita, shocked film audiences in the early 1960s, on the eve of the Sexual Revolution and the Women’s Liberation Movement, for in those days a Valium-laced, kaffeeklatch mentality still held sway. The impact of the literal and cultural censorship of the day straight jacketed Stanley Kubrick, severely limiting what he could show. Had he known how bad the censors would get, the director said, he’d never have tried to make the film.

Mason’s performance is a classic. Peter Sellers does some remarkable shapeshifting. And Sue Lyon (Lolita), who celebrated her fifteenth birthday during principal photography, holds her own with Mason, Sellers, and Shelley Winters—no small feat.

Nabokov’s screenplay, however, suffers from several grave mistakes. The brilliant but distracting scenes that showcase the chameleonic genius of Peter Sellers, as Lolita’s true crush Clare Quilty, derail its primary plot. Worse, the writer excised both the incidence of unbearable loss in Humbert’s adolescence that branded the scholar’s psyche with hebephilia for life—and the death of Lolita in childbirth at the age of 17—the two elements that gave the book such tremendous dimension. These crucial scenes provided both the context of Humbert’s possession and the final, fatal loss that ultimately kills him. Nabokov’s script robs Humbert of his desperation, ecstasy, and fear—and it also steals away the character’s poetic voice. These are errors that Stephen Schiff, the writer/director of the 1997 remake, will not duplicate.

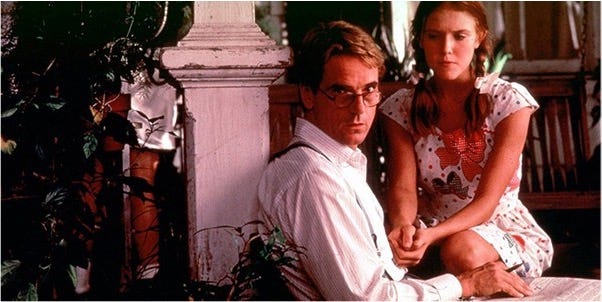

Jeremy Irons as Humbert Humbert

Lolita (1997)

Samuel Goldwyn Company. Screenplay by Stephen Schiff from the novel by Vladimir Nabokov. Directed by Adrian Lyne. With performances by Jeremy Irons, Dominique Swain, Melanie Griffith, and Frank Langella.

Offering the opinion that this is a better film than the original is blasphemous. People you don’t even know scurry about collecting the raw materials of your imminent demise: desiccated twigs and tree limbs, tins of Kingsford, and boxes of safety matches.

But it is a better film: The performance by Jeremy Irons is haunting and gorgeously modulated. Dominique Swain is half a dozen characters simultaneously—a beautiful, taunting, seductive, manipulative, and damaged sexually precocious child-woman. Her desperation shows in the cache of money she hoards for an escape and in an incidence of uncontrollable sobbing she endures after making love (if you can call it that) to Humbert.

Whereas the original film’s shooting script robs Humbert of his poetic voice, Schiff graces his damned scholar with some of the most beautiful language from Nabokov's extraordinary book. In doing so, he provides Humbert with a character arc of traumatic imbalance leading to obsessional behavior that culminates in profound regret—and a strange, short-lived healing.

Schiff is almost perfectly true to Nabokov’s written words in Humbert’s last encounter with the teenager whose life he broke:

HUMBERT: I looked and looked at her, and I knew, as clearly as I know that I will die, that I loved her more than anything I had seen or imagined on earth. She was only the dead-leaf echo of the nymphet from long ago—but I loved her, this Lolita, pale and polluted and big with another man’s child. She could fade and wither—I didn’t care. I would still go mad with tenderness at the mere sight of her face.”

And as Humbert waits upon a hill to be arrested for his brutal murder of Clare Quilty, he muses at the sounds coming from the mining town below him.

HUMBERT: What I heard then was the melody of children at play, nothing but that. And I knew that the hopelessly poignant thing was not Lolita’s absence from my side, but the absence of her voice from that chorus.

This is a quintessential cinematic demonstration of Jung’s point that an archetype—and every truly archetypal character—is always, but always, both positive and negative simultaneously: Humbert was once a decent human being. Though tormented by the most agonizing of internal pressures, he remained a good man for a very long time. In Lolita’s presence, his will failed, and his psyche descended into its darker nature. He ends a manipulator, statutory rapist, liar, and killer. Still, he has the goodness to feel regret, to experience the impact he has had on her life. For her part, she has destroyed him in equal measure.

In the end, Humbert believes that the story he writes in prison will be the only immortality he and Lolita will ever know. And he is right. The rest, as Nabokov would say, is “rust and stardust.”[ii]

Perhaps the strangest honor for a book or a film is to be banned. Esther Lombari of ThoughtCo assembled a list of the ten most-often-banned classic novels. It includes Ulysses by James Joyce, The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger, The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, The Color Purple by Alice Walker, Beloved by Toni Morrison, The Lord of the Flies by William Golding, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, and 1984 by George Orwell. And the last? Lolita.

Read the book. Then see both films. Then wonder, for a very long time, how Nabokov ever came by the insight to write such characters as these.

[i] Izzard, Suzy (as Eddie Izzard). Dress To Kill. Epitaph. Produced by Charlie Swanson, Eddie Izzard, Lawrence Jordan. 1999.

[ii] Nabokov, Vladimir. The Annotated Lolita: Revised and Updated. With an introduction, preface, and notes by Alfred Appel, Jr. 1999: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. Location 5419.

I love that someone else is interested in these versions of “Lolita.” I used to teach a course on the book, the screen adaptations, and how the Lolita archetype persists in cultural representations. It was one of the most enjoyable courses I taught during my years of university teaching. I don’t agree about the remake being better than the Kubrick, though. I’m going to look for a link to something I wrote that will interest you!!

Lovely review, Morgaan. Thanks. I've seen the original several times, and read the book, but never the '97 version. I'm a Kubrick fan of longstanding and I suppose I didn't want my admiration tarnished, even a little. I'll fix that now.

I'm proud to have read all ten banned books! re: The Grapes of Wrath: I lived for long stretches when I was a young boy with my grandfather, who was a widower. We lived in the same house he'd built in the New Mexico Territory well before statehood, alongside the wagon trail he'd followed west from Tennessee, which became the original roadbed of Route 66. Our adobe and frame house consisted of four rooms built atop what was originally a half-dugout, characteristic of early plains dwellings. We had no running water and only got electricity when I was about five. There was a water pump in the front yard (called the door yard in them days) and another out back behind the kitchen. The toilet was a two-holer reached through the chicken yard, about 50 yards in back. There was a large rooster who patrolled the yard, just waiting to chase me to and from the outhouse. He scared the bejesus outta me. He always referred to us as a couple of old bachelors, even when I was just a kid.

We used to take long walks together through the mesquite and piñon speckled hills round about the place. The nearest house was the better part of a mile distant. There were mazes of sand hills that had been formed by dirt blowing westward from Texas and Oklahoma in the 30s, and catching around the bases of the mesquites. Grandfather would poke around in the sand hills and show me the artifacts abandoned there - a rusted-out blue enameled coffee mug, a busted fan belt, a tattered and yellowed bible in a box once. He explained to me that California bound dust bowl refugees traveling on 66 would camp the night in those little pockets of shelter provided by the very dust they were escaping and sometimes come sheepishly to the door, asking for a little milk for their babies (he always kept a few cows) or to fill a flax water bag at the pump.

When I was about 11 or 12, he handed me a bigger book than I'd ever read before. It was The Grapes of Wrath. And I can hear his voice today (I often do) saying, "Read this, Boy. It will teach you everything you ever need to know about compassion." He never called me anything but "Boy" or "The Boy," in the third person. And I was his boy, but he made me a man.

Thanks for giving me cause to remember that.